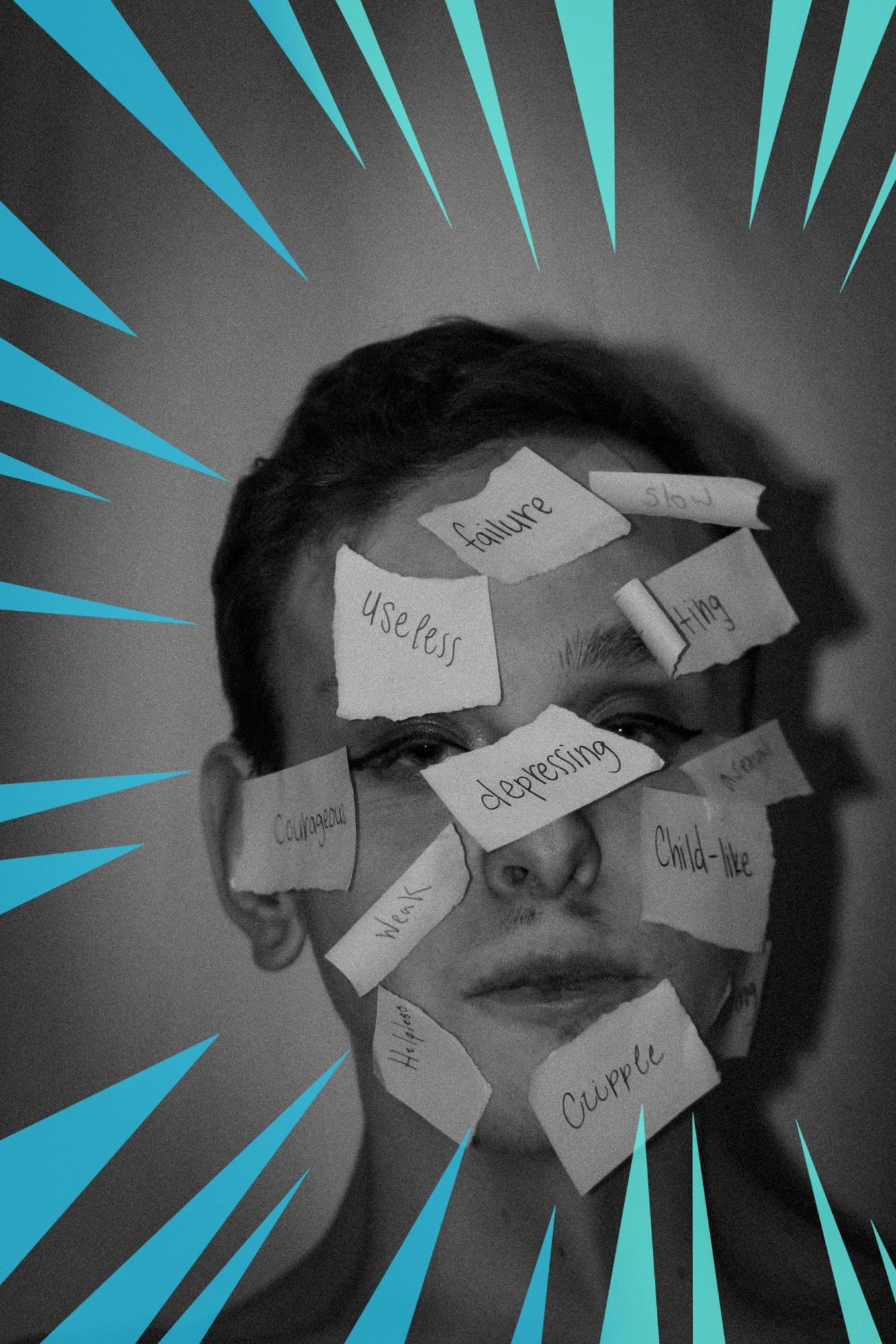

Break the Spell of the Inner Critic

One simple shift to change the conversation

You’re wasting your time. Everything you do turns out wrong.

Ugh, my inner critic’s words tighten my chest and freeze my fingers over the keyboard as words clog in my throat. A little nauseous, I want to give up. Another voice tells me to quit being a baby. None of these sentiments are actually helpful. They’re not providing guidance or advice. They just want me to quit. But wait a minute - who exactly is talking?

The Problem With Inner Statements

Your inner critic speaks with authority so you’ll listen. It sounds like Truth; plain facts in black and white. No ambiguity, nuance or room for debate, these judges are hard to ignore and even more difficult to oppose.

Acceptance and Commitment Theory (ACT) describes this experience as cognitive fusion - the tendency to take thoughts literally and remain in problem solving mode, even when it’s not helpful. Your mind tangles in the past or future and derails whatever you were just doing. The more you ‘merge’ with these thoughts, the less free your thinking. Cognitive fusion tanks your mood and stops you in your tracks. Surprisingly, it’s a coping mechanism, anticipating and heading off unpleasant emotions or memories. But it’s outdated and rigid. As a result, you lose touch with the part of you that creates, dreams, wonders and grows.

The inner critic chimes in and your nervous system reacts like it’s carved in stone. Listening to it, giving it weight and power, just makes you spin your wheels.

The Tiny Shift That Breaks the Spell

You only need to add two words to the inner critic’s statement to burst the bubble: “I think…”. Add this to anything the inner critic says and see how it changes the phrase.

You’re wasting your time. → I think you’re wasting your time.

Everything you do turns out wrong. → I think everything you do turns out wrong.

Try it with the familiar phrases your inner critic says. It transforms the words from statement of fact to an opinion. Does it feel different to say these things out loud? An opinion gives you something to work with; a nugget to debate, challenge or ignore. The shift gives you the ability to actually work with it in your head.

Why This Works (Nerdy Brain Science Alert)

Converting the statement to opinion breaks the cognitive fusion spell by considering it an externally generated event. It becomes something said to you, not from within you. This is metacognition, thinking about thoughts, and is processed differently in your brain, interrupting the fusion spiral. You weaken the ‘Truthiness’ of the statement and allow the space to see it as an experience - This is what I am thinking right now.

De-identification with the I

Here’s a question for you - who is the “I” in the words “I think you’re….”? What voice is speaking to you at this moment? What evidence does it give to support the claim? Why should you trust this particular narrator? Is there counterevidence that makes you lean towards a more accurate truth?

We can use the parts metaphor from Internal Family Systems (IFS) to get to the root and figure out what the Inner Critic is trying to do. Does it want you to feel bad for no reason or might it have an ulterior motive? Since they are parts and not actual people, their knowledge scope is limited and tends to skew towards less sophisticated tactics. They won’t reason with you so arguing with them is a black hole of wasted time. They have one agenda - keep you from getting hurt at all costs, even if that means making you small and withdrawn. In their logic, if you don’t take risks, you won’t be disappointed.

Critically Evaluating the Inner Critic

Let’s take the two statements from before - You’re wasting your time and Everything you do turns out wrong. Is there a trigger that prompts you to speak to yourself this way? Did you feel scared, anxious, intimidated, judged, or excluded? What sort of events would this part feel the need to protect you from? How and when do these voices pipe up? There is likely a pattern.

The first clue that cuts into the legitimacy of these statements is their “forever” quality. They make sweeping generalizations about how you spend your time and the results of your efforts. Is it accurate that everything you do turns out wrong? Can you think of examples where you did things right? You’re still here, aren’t you? You must have kept yourself alive pretty well so far.

If it’s equally true that you sometimes use your time wisely, it can’t also be true that you always waste your time. Breaking down the credibility of these claims by seeing other sides further undermines the truthiness and neutralizes the criticism. Now, if there’s some legitimacy to these statements, you can analyze them without judgement and decide what you’d like to do differently.

Tools for Your Toolbox

Here are a handful of useful cognitive distancing techniques to try out. If one doesn’t work, try another.

1. “I’m having the thought that…” - Turns a statement into an observed mental event.

2. Add “I think…” - Converts certainty into opinion.

3. Third-person self-talk - Refer to yourself by name instead of “I.”

4. Label the voice - Name the part (e.g., “Inner Critic,” “Prosecutor”).

5. Write the thought down - Put it on paper; move it physically away.

6. Put the thought on an object - Imagine it printed on a sign, screen, or leaf.

7. Add time - “This is a thought I’m having right now.”

8. Future-self perspective - Ask what you’ll think about this in five years.

9. Change the voice - Say the thought in a cartoon or exaggerated tone.

10. Slow the thought down - Repeat it very slowly to interrupt automaticity.

11. Ask what the thought is protecting - Shift from truth to function.

12. Values reorientation - “If this thought weren’t in charge, what would matter right now?”

A Real Life Dialogue

How I talk to myself when one of these voices interrupts my writing:

Trigger: Sitting down to write.

Voice: Ugh, you’re writing again. You’re too academic and preachy. You don’t even know how to write in a way people actually want to read.

Me: (Mentally adding, “I think you’re…in front of the voice) Oh, hey there. You again with your opinions. You know you’re not actually helping me, right?

Voice: You know I’m right. Look at your subscriber count. You secretly want to go viral and heal the world. So arrogant.

Me: Well, your evidence is compelling. It’s true that I don’t have millions hanging on to my every word but I’m okay with that. And while I’d love to heal the world, I know I’m only one person and there are lots of people aiming in the same direction. I don’t think that qualifies as arrogant but I’ll keep an eye on it.

Voice: Whatever, you’re in denial.

Me: That’s always a possibility…which is why I reflect and ask people I trust to give me feedback.

Voice: Well, you’re…..

Me: Ok, that’s enough. I’ve got to get back to writing. Bye!

I’ll spare you the numerous conversations where I’ve thanked the voice for it’s service, reminded it that I’ve taken risks before, and lovingly reassured it that I’m okay with putting myself out there. I’ve got lots of practice tucking this voice back in the box. Because it can’t use adult reasoning, engagement just makes it meaner. It’s only convinced when I use adult methods of protection. I earn it’s trust by standing up for myself.

Reframing the Relationship with the Inner Critic

Inner voices use a set of basic crayons with no sharpener. You’ll default to them unless you upgrade. Decide to find and use adult strategies. Work with all the little kid parts and their unsophisticated worries and strategies. Reframe and interpret the voices as signals to calm and reassure yourself. Clear the path. The world needs your contributions and it’s up to you to find the way.

Excellent breakdown of cognitive fusion. The "I think..." trick is deceptively simple but changes everything, kinda like putting quotes around someone elses opinion instead of letting it become your internal narration. I've noticed the inner critic gets louder during transitions or when stakes feel high, probably because that protecitve part thinks its helping. The part about de-identifying with the "I" is where it really clicked for me tho.

Thank you for sharing these tools with us. Great strategies that I shall use more often.